Introduction

I have always been fascinated by how the language of comics expresses the flow of time indirectly—through static images.

How?

As a rule of thumb, it combines two basic but core principles:

space = time(space equals time)time ↔ reading(time is related to the reading experience)

Before detailing these principles, it’s important to note that in any piece of sequential art1, these two principles cannot be clearly separated. Instead, they combine seamlessly, forming a gestalt.

Space = time

Let us focus on the first principle: space = time. The language of comics expresses the flow of time by sequencing space. It sequences space at three different levels, from highest to lowest:

- space/time is structured in a sequence of pages

- space/time is structured in a sequence of panels within a single page

- space/time is structured in a sequence of elements within a single panel

Sequence of pages

How is space/time structured in a sequence of pages?

In a sequence of pages, each of the pages (usually) works as a macro unit of meaning that moves the story and action forward.

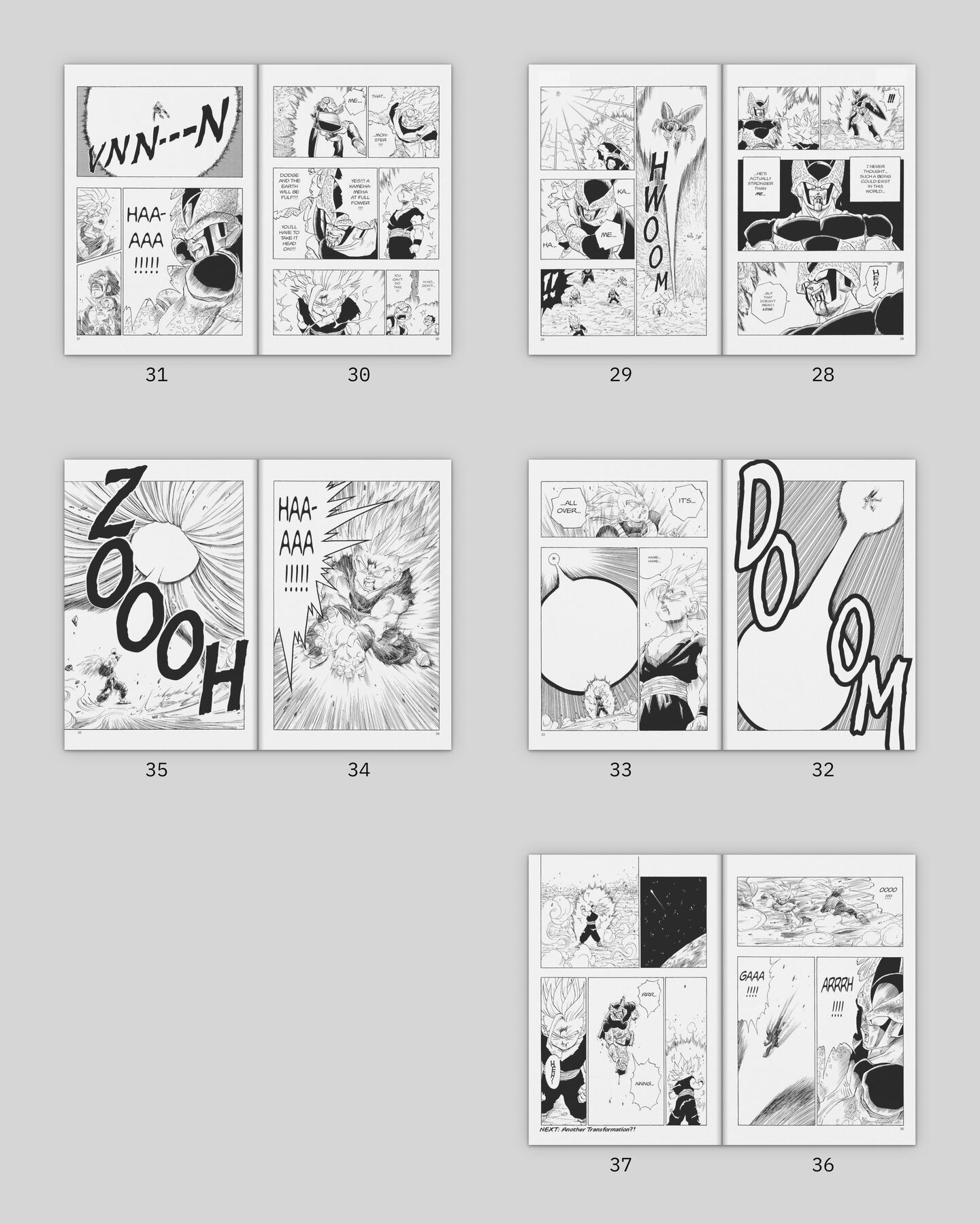

Let us look at a sequence of pages from the manga Dragon Ball by Akira Toriyama as an example. In this sequence, Gohan—Goku’s son—counterattacks to prevent Cell—the mashed up villain—from destroying Earth.

Pages 28–37, taken from the chapter 410 The Ultimate Kamehameha from the manga Dragon Ball by Akira Toriyama.

If we go through the above sequence and roughly time how much each page covers:

| Page/s | Event/s | Time |

|---|---|---|

| 28–30 | Uh-oh. Cell is charging a huge Kamehameha 2. Things are about to go south. | ∼32s |

| 31 | Cell launches the wave towards Earth. How foolish of him! If Gohan dodges it, Earth will be nuked. | ∼2s |

| 32 | Oh my gosh! Cell’s Kamehameha is too powerful. There is no way Gohan can survive the hit. How will he bail us out? | ∼1s |

| 33 | Hold on. Gohan is charging a Kamehameha as well. Maybe there is some hope. | ∼4s |

| 34 | Also Gohan launches his wave! suspense | ∼2s |

| 35 | Hurray! Gohan’s Kamehameha overpowers Cell’s! | ∼1s |

| 36–37 | Take this, Cell! That’s what you get for messing with the wrong folks. | ∼8s |

We can conclude that the entire sequence spans a time of more or less ∼50 seconds.

As mentioned before, we should always keep in mind that these ∼50 seconds are not a product of just the sequence of pages in itself, but rather the outcome of mixing the two principles space = time (at the level of pages, panels, and elements) and time ↔ reading in different quantities.

Sequence of panels

How is space/time structured in a sequence of panels within a single page?

In a sequence of panels, each panel (usually) represents a distinct event in time, and each gutter—the void space between panels—advances time forward from one panel to the next.

The amount of time a gutter represents is derived from the events in the adjacent panels it separates. The further apart these events are in time, the longer the time the gutter expresses.

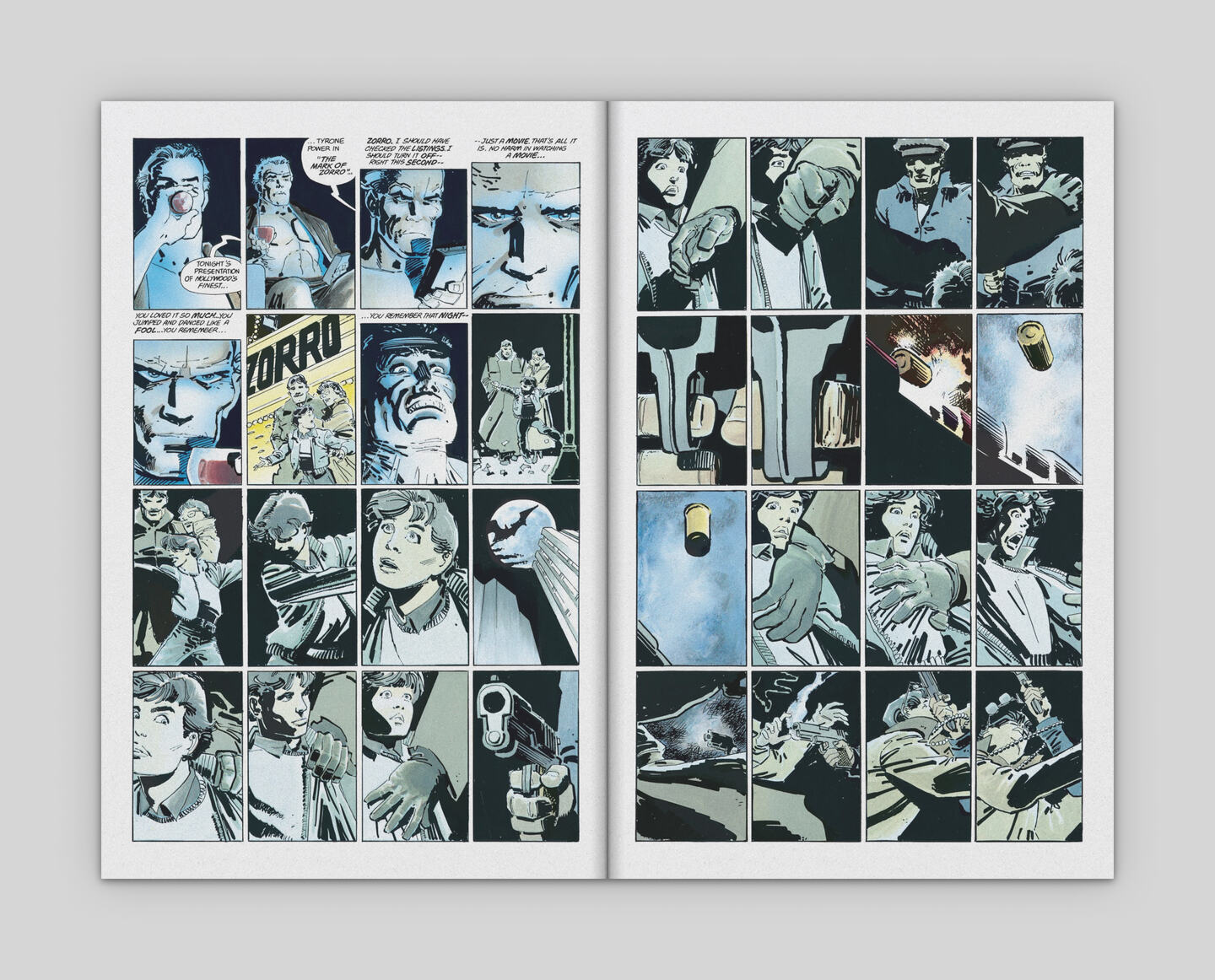

Let us look at a sequence of panels from the graphic novel The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller as an example. In the spread, Bruce Wayne—also known as Batman—has a flashback where he remembers his parents being killed during an armed robbery.

Pages 16–17, taken from The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, and Lynn Varley.

In the above spread from The Dark Knight Returns, the events represented in the panels are quite close to each other in time.

This results in the time expressed by each gutter being rather uniform and condensed, making the entire sequence of panels feel like a cinematographic slow motion 3.

Sequence of elements

How is space/time structured in a sequence of elements within a single panel?

In most cases, a sequence of elements in a panel represents events that happen simultaneously.

However, in particular cases, elements juxtaposed in a panel can represent simultaneous yet distinct events, “stretching” the time expressed within a space that is otherwise perceived as continuous.

Let us look at a panel from the comic book Asterix And The Banquet by René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo as an example.

The first panel of page 6, taken from Asterix And The Banquet by René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo.

In the above example, the first panel of page 6 from Asterix And The Banquet depicts three distinct events that, technically 4, happen at the same time:

| Position | Event/s |

|---|---|

| Left | Two women are having a conversation. |

| Center | A man is leading a cart to carry hay. |

| Right | Obelix talks while Asterix peels a few potatoes. |

However, since they are juxtaposed in space one after the other and we read them from left to right, we perceive them as happening one slightly after the other.

Jumping through three different events within the same panel makes its perceived duration much longer than if another panel of the same size and shape were to represent a single event. The panel from Asterix And The Banquet ends up feeling like a cinematographic pan shot 5.

Time ↔ reading

Let us now focus on the second principle: time ↔ reading. The language of comics expresses the flow of time by speeding up or slowing down the reading experience.

As a rule of thumb, the more time we spend reading a sequence of pages, panels, and/or elements, the longer we perceive its “duration”.

How can we influence the reading experience? Usually, in two ways:

- the more visually complex a sequence is, the more time we need to digest it, and vice versa

- the more speech balloons a sequence has, the more time we need to read it, and vice versa

Visual complexity

How can visual complexity influence the reading experience?

Again, the more visually complex a sequence is, the more time we need to digest it, and vice versa.

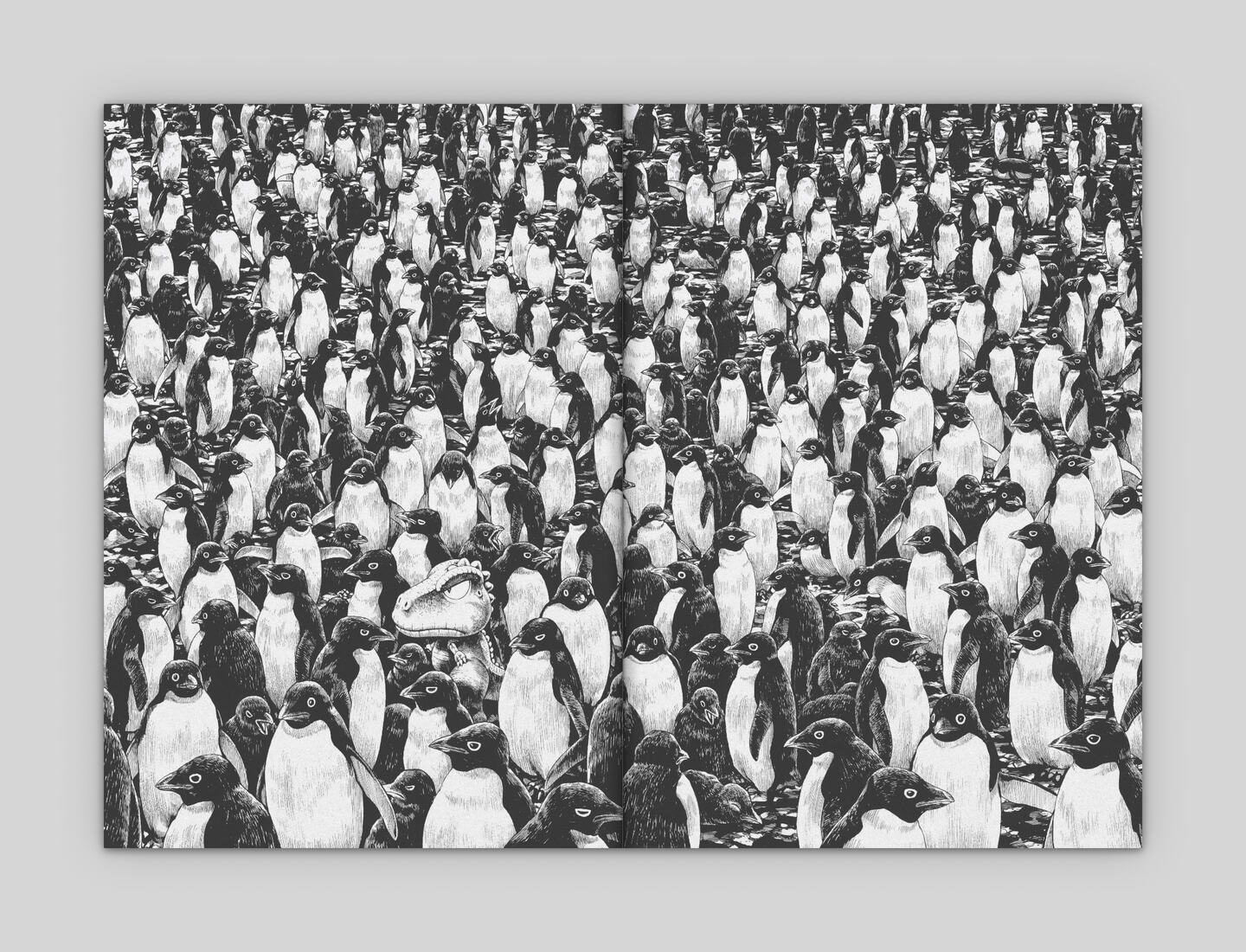

Let us look at a spread from the manga Gon by Masashi Tanaka as an example. In volume 2, chapter 8, Gon the dinosaur tries to blend in and live with a colony of penguins.

Pages 7–8 taken from volume 2 chapter 8 Gon Lives with The Penguins from Gon by Masashi Tanaka.

In the above example from the manga Gon, by the time it takes us to find the main protagonist lost in the waddle of penguins, we end up feeling as though the little dinosaur has been living with the colony for quite a while.

Speech balloons

How can speech balloons influence the reading experience?

Again, the more speech balloons a sequence has, the more time we need to read it, and vice versa.

Let us use a panel from Sin City: The Hard Goodbye by Frank Miller as an experiment and play with the speech balloons of Marv, the protagonist, who is about to get wasted.

The first panel of page 2—modified!—taken from Sin City: The Hard Goodbye by Frank Miller.

In the above example, the first panel of the page is modified: Marv’s speech balloons have been removed, and the panel does not have any dialogue.

Let us compare its reading experience with the one of the below example, where the same panel is left unmodified: Marv’s speech balloons have not been removed, and the panel preserves the original dialogue.

The first panel of page 2—unmodified!—taken from Sin City: The Hard Goodbye by Frank Miller.

Reading the balloons in the unmodified panel slows our reading experience: Marv turns from taking a sip from a bottle to getting wildly drunk.

Recapitulation

As illustrated by the above examples, the language of comics can express the flow of time indirectly—through static images—by combining seamlessly these two core principles:

space = time(space equals time)time ↔ reading(time is related to the reading experience)

-

Comics can be defined as sequential art: the arrangement of pictures or images and words to narrate a story or dramatize an idea—a definition created in 1985 by Will Eisner and expanded in 1994 by Scott McCloud. ↩

-

The Kamehameha is the signature energy wave of the Dragon Ball series. ↩

-

Technically because they are juxtaposed in the same continuous space enclosed in a panel, without any gutter or page break separating them. ↩

-

See pan shot in Wikipedia. ↩