- What is JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure?

- Spoiler alert!

- The zenith of the series

- A few premises on mangas

- The flow of time in the language of comics

- The sequence of pages

- The sequence of panels and their elements

- The closure

What is JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure?

Hirohiko Araki (7 Jun 1960) is a mangaka and author of one of my favorite Japanese manga: JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure. The manga started in 1987 and continues to this day, spanning 8 series with a total of 131 volumes, and counting.

JoJo tells the adventures of the Joestar family and follows their struggles against the series’ core villain, Dio Brando, and his legacy.

The main characters in JoJo can generate spiritual entities, named Stands, which help their owners with various superhuman abilities.

Spoiler alert!

While I will try my best to keep spoilers to a minimum, I cannot avoid revealing a major plot event from JoJo’s 3rd series—Stardust Crusaders. As a matter of fact, in this piece, I am interested in analyzing how Araki pushed the language of comics to the limits to represent that very event.

So, spoiler alert!

The zenith of the series

As a teenager, I considered the final showdown between the Joestar family and Dio Brando at the end of the 3rd series to be the zenith of the manga.

Even now, 20 years later, I still rejoice while re-reading Dio’s World Part 1–18. Among all of the best moments of the 3rd series, the battle between Dio Brando (stand → The World) and one of the Joestar party members, Noriaki Kakyoin (stand → Hierophant Green), remains one of my favorites.

Why?

The subject of Dio’s World Part 7 is indeed intriguing. At the end of a tense chase, Dio engages Kakyoin in battle. Kakyoin has Dio on the ropes and forces him to reveal (finally!) the secret of his stand: the ability to stop time for everyone except its owner.

Fascinated by Araki’s skills, I have always asked myself, “How was Araki able to convey the stoppage of time in a sequential art medium like comics that, by its own nature, can only convey the passage of time indirectly, by juxtaposing static images?!?”.

This article is my attempt to find an answer.

A few premises on mangas

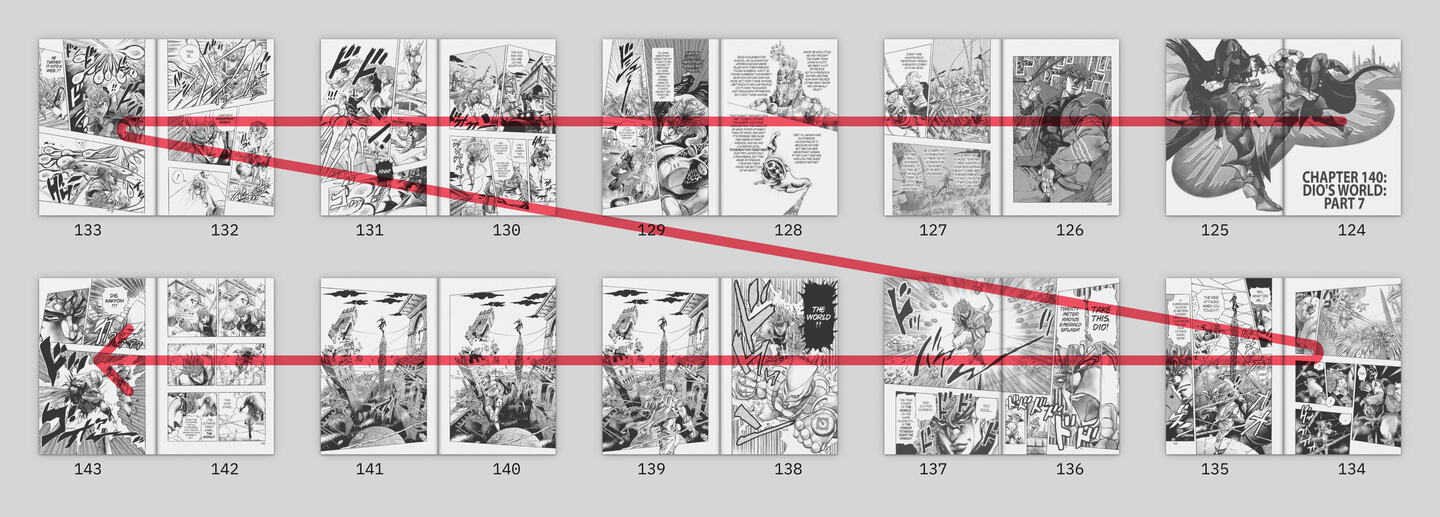

In this piece, I focus my analysis only on Dio’s World Part 7, a chapter that consists of 20 pages in total, laid out two by two in 10 spreads 1.

Since JoJo is a manga, its reading direction is reversed compared to Western comics. In a manga, you read pages starting from the right-hand page, corresponding to the end in Western comics, and you leaf through them backward, toward the left-hand page, corresponding to the start in Western comics:

Similarly, you read panels within a page, as well as elements within a panel, from right to left and top to bottom:

The flow of time in the language of comics

Before analyzing how Araki approached conveying the stoppage of time in Dio’s World Part 7, we should first brush up on our language of comics.

How does the language of comics express the flow of time? As a rule of thumb, by combining two basic but core principles:

space = time(space equals time)time ↔ reading(time is related to the reading experience)

Space = time

Let us focus on the 1st principle: space = time. The language of comics expresses the flow of time by sequencing space. Overall, it sequences space at three different levels. From highest to lowest:

- space/time is structured in a sequence of pages

- space/time is structured in a sequence of panels within a single page

- space/time is structured in a sequence of elements within a single panel

Time ↔ reading

Let us now focus on the 2nd principle: time ↔ reading. The language of comics expresses the flow of time by speeding up or slowing down the reading experience.

As a rule of thumb, the more time we spend reading a sequence of pages, panels, and/or elements, the longer we perceive its “duration”.

How can we influence the reading experience? Usually, in two ways:

- the more visually complex a sequence is, the more time we need to digest it and vice versa

- the more speech balloons a sequence has, the more time we need to read it and vice versa

The sequence of pages

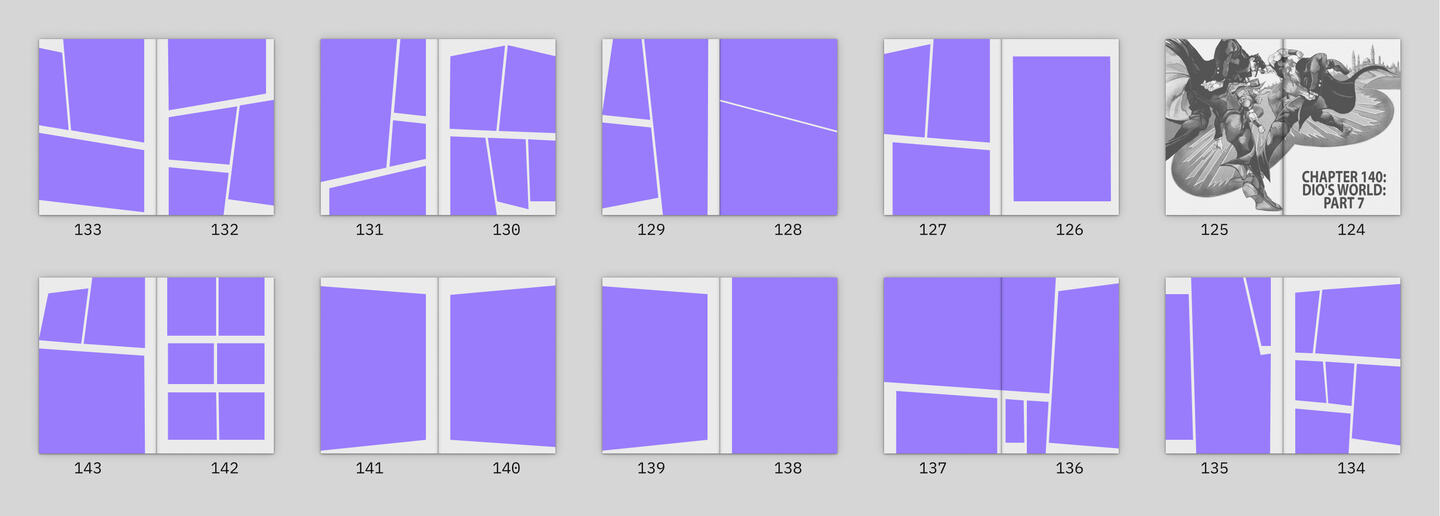

Let us start by having a look at the sequences of pages in Dio’s World Part 7. As in any action comic worthy of its name, pages in the sequence are mostly composed of multiple panels of various sizes, shapes, and slants.

Since almost all of the panels in the sequence represent a distinct action in a distinct moment in time, and since most of the pages in the sequence are composed of multiple panels, a lot of panels/actions per page involve a fast-paced narrative rhythm.

More panels → more actions → faster tempo.

But what happens when we reach page 138? The number of panels/actions per page drops drastically: from an average of 3,25 panels/actions per page on pages 126–137, we get to an average of 1,00 on pages 138–141, to get back again to a higher average of 4,50 on pages 142–143.

What is the deal with pages 138–141?

In these pages, Dio reveals his power and lets his stand, The World, stop the time for the first time.

So, how does Araki convey the stoppage of time at the level of the sequence of pages?

He first hastens the narrative tempo by having a high number of panels per page before the major plot event on pages 126–137, and then he purposely slows it down by abruptly decreasing the number of panels per page so that one and only one panel corresponds to each of the four pages 138–141.

But that is not all. He further slows the narrative tempo down by purposely stretching the length of one single action—the first few steps that Dio takes in the frozen time to engage Kakyoin and get him into the radius of action of The World—into three of those four pages.

An action that lasts just a couple of seconds is thus represented on three different pages, dilating our perception of time. By comparison, the actions in the pages immediately before (pages 134–137) last at least 20+ seconds in total.

The cliffhanger

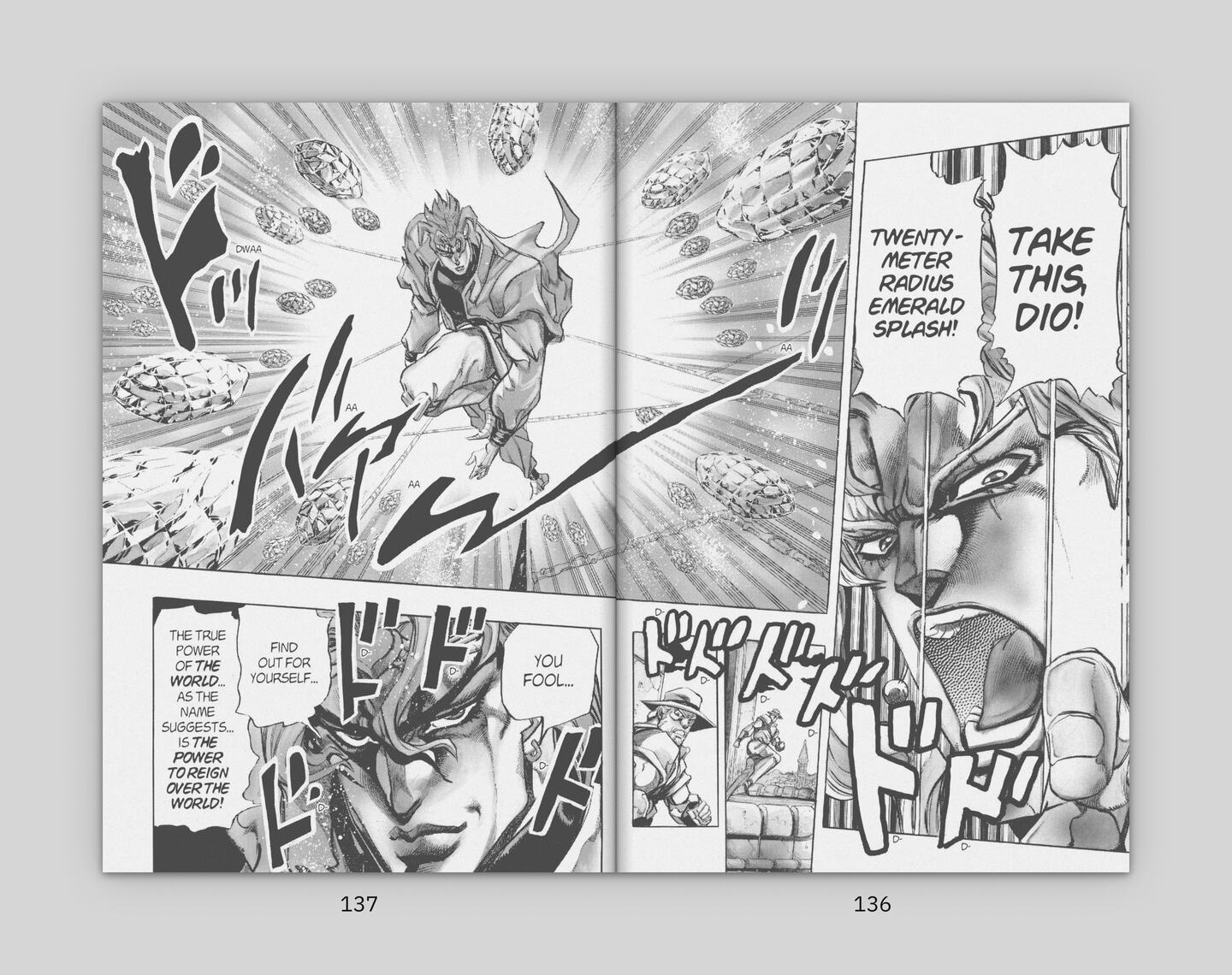

And just to put the icing on the cake, Araki builds a cliffhanger on pages 136–137—right before the big revelation.

After having a confident Kakyoin deliver a line that seems to anticipate his victory over Dio at the beginning of page 136, Araki closes the spread by letting an all but frightened Dio Brando utter a sentence that forewarns a potential overturning of the situation in the very last panel of the left-hand page 137.

Since page 137 is the last page in the spread, we readers have to turn the page to move the plot forward and learn what Dio will do.

The suspense caused by the cliffhanger indeed motivates us to reach the next page, but it also contributes incidentally to further dilating our perception of time. Turning that paper page becomes particularly “heavy” as we perceive it as an obstacle that slows down our reading experience.

The sequence of panels and their elements

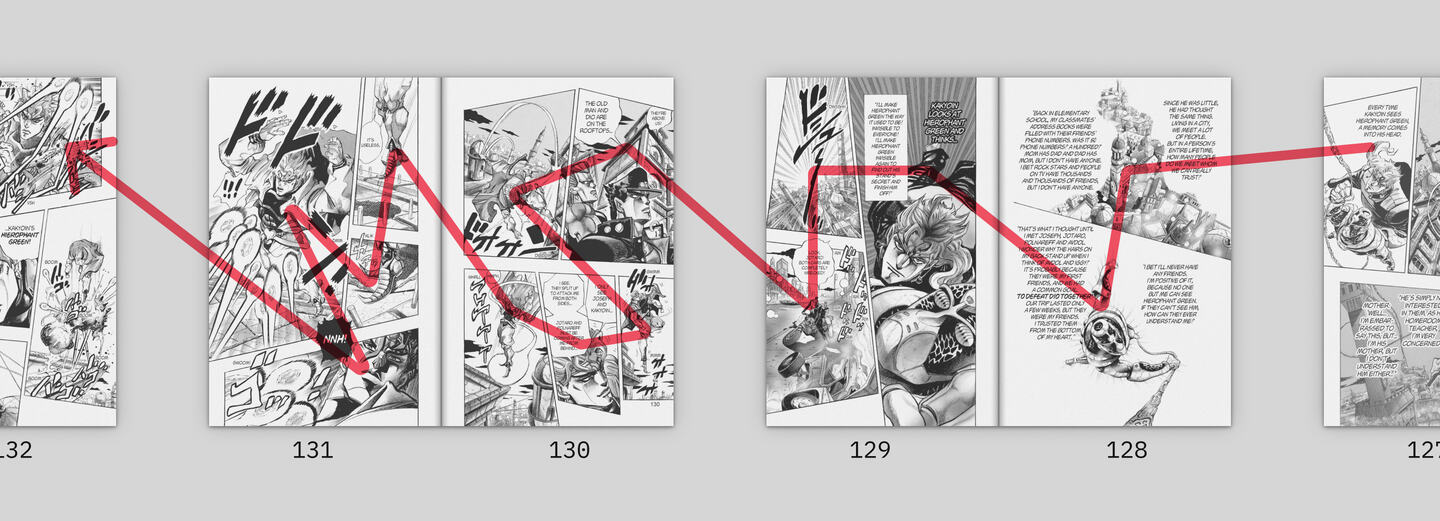

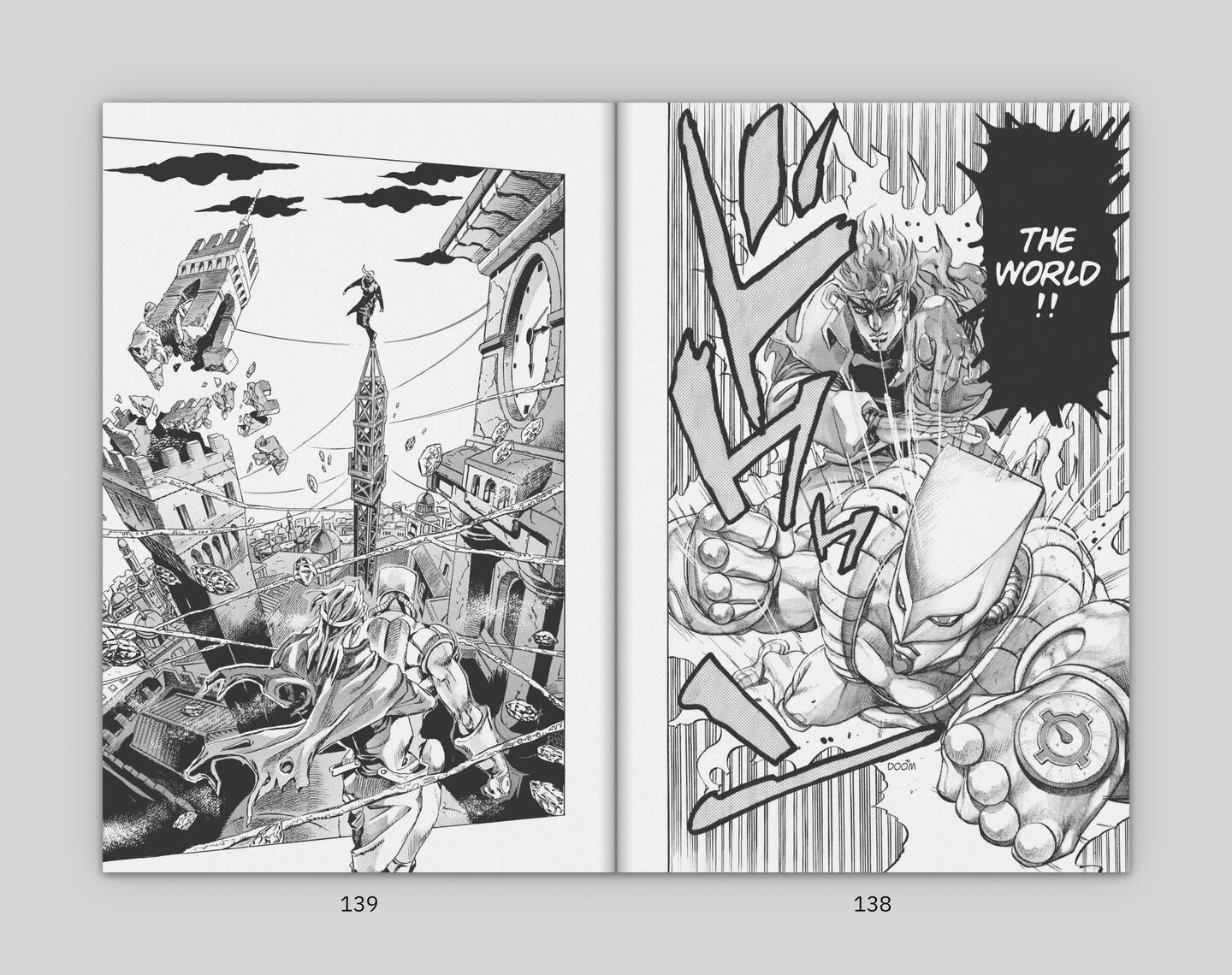

Let us further focus on the sequence of panels and elements in the panels on pages 138–141. As already mentioned, each of these pages coincides with a single, full-page panel.

The first full-page panel on the right-hand page 138 shows us the exact moment in which Dio Brando and The World stop the time. From the first glance, the panel looks quite different not only from the next three full-page panels but also from the rest of the panels in Dio’s World Part 7:

- it is the only panel in the chapter that has no gutters at all and extends beyond the trim area of the page

- it is the only panel that has a speech bubble with inverted colors, its text in white and bubble in black

- its background, void of details, is a mass of motion lines that lets us fully focus on the plastic pose taken by the two characters

By standing out from the others, it indeed better highlights the key action it represents. However, its dissimilarity has also a secondary effect. Since the panel and its elements have a few traits that we readers are not much used to, we require a bit more brainpower—and thus a bit more time—to fully process them.

Moreover, the drawing, a pleasure for the eyes, is one of the rare moments in which, as readers, we have the chance to see The World projected in its entire majesty.

It is a Wow! drawing for a Wow! moment. Its beauty catches our attention and makes our eyes linger on the page more than usual, further slowing us down.

The second full-page panel on the left-hand page 139 is, on the other hand, quite a different one. It is almost a reverse shot where we can see the Cairo skyline and Dio from behind, staring at Kakyoin. Judging by his pose, not more than a fraction of a second has passed since the preceding panel. However, the abundance of details in the background makes our eyes linger even more, and that fraction seems to last much longer.

There is no onomatopoeia, so silence is king. Kakyoin’s balance is precarious. A minaret is falling with no dust. Dio is literally out of the panel frame as if he were staring at a static painting. Araki gives us a lot of hints about what is going on, but we do not get it quite yet since, until now, as first-time readers, we have no clue about Dio’s superpower.

Not until we reach next spread, pages 140–141. Everything in the full-page panel on page 140 looks the same as on page 139. Frozen. Kakyoin’s balance is still precarious. Nothing has moved. Nothing but Dio Brando. That b*****d got rid of his rags, opened a gap in Hierophant Green’s minefield, and is now approaching Kakyoin.

The full-page panel on page 141 is just the same. Still frozen. Dio’s rags are suspended in mid-air. Yet Dio Brando took another few steps, and he is halfway from Kakyoin, who still stands in precarious balance, out of touch with the world. “What’s going on?!?” we ask ourselves.

Disoriented, we glance back and forth between pages 140 and 141, trying to solve the riddle. Both pages seem to look alike until we realize that they are not.

I like to imagine that Araki put these two pages in front of each other on purpose, to let us play spot the differences and further spend time on the spread. And the fraction of time that it takes Dio to jump from a dome to a tower becomes an eternity in our inner time, while we look at the effects of his sky walk, slowly realize what he has done, and worry about the potential aftermath.

The closure

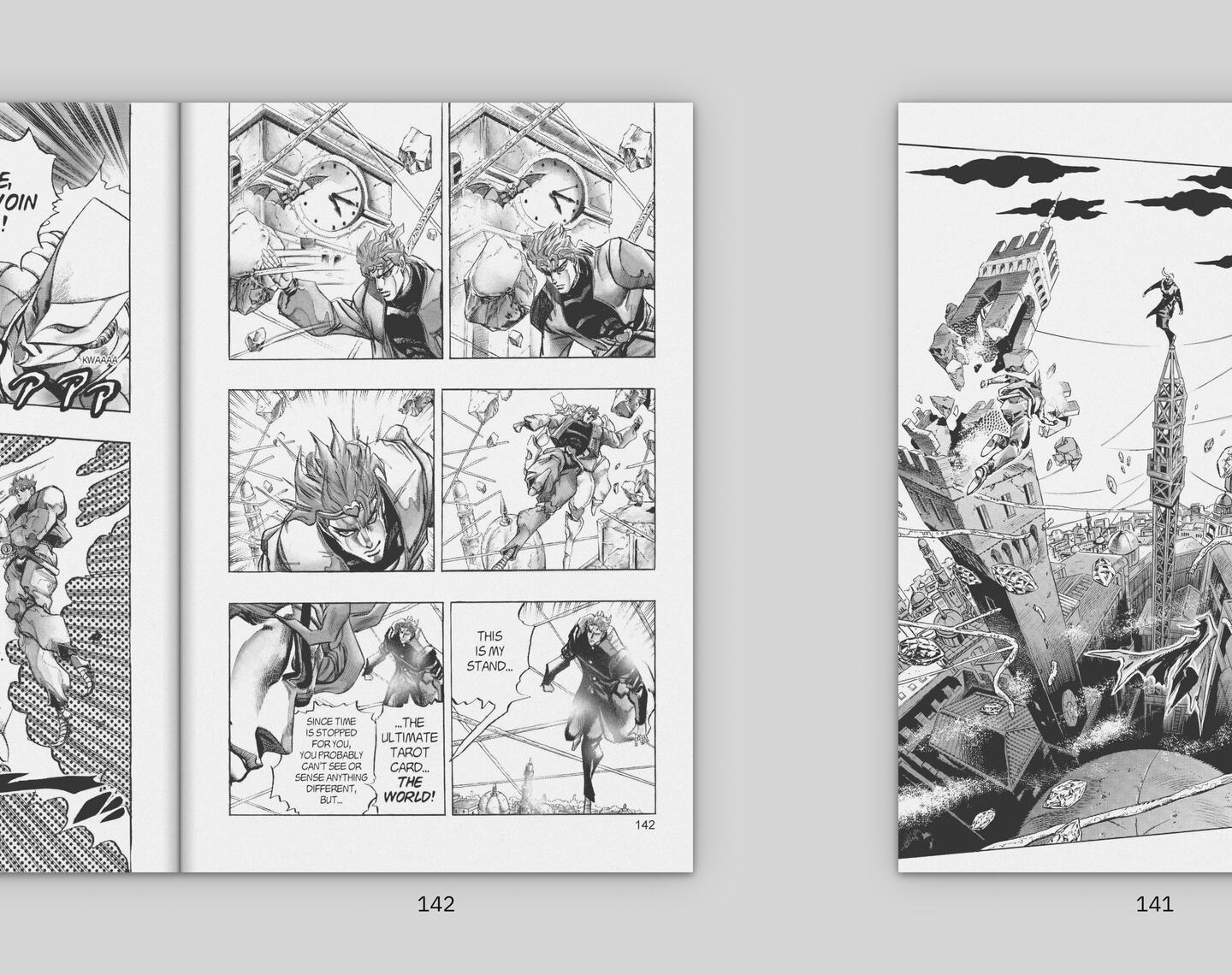

After the peak of the climax, Araki makes everything clear in the last spread in Dio’s World Part 7, where the narrative rhythm returns to the usual, with an average of 4,50 panels per page.

Page 142 has six panels, coupled two by two.

The panels in each pair share the same camera angle and thus point to the same frozen, unchanging background. While Dio moves between frames, everything else stays immutable.

In the first two panels of page 142, Dio moves a rock out of his path. A still clock is well framed in the center of the panel. Its hands do not move.

In case it is not clear enough, in the last panel of the page, Araki has Dio explicitly declare that time has stopped. Dio is now one step closer to Kakyoin, who is still out of touch with the world….

-

In a printed book the right-hand page is called the recto and the back of it, a left-hand page, is called the verso. A double page of a verso and a recto is called a spread.

Read more on Western Layout Requirements / Pages at Wikipedia. ↩